[Shellcode x64] Find and execute WinAPI functions with Assembly

TLDR: NASM source code here (well documented, easy to read).

What you will learn:

- WinAPI function manual location with Assembly

- PEB Structure and PEB_LDR_DATA

- PE File Structure

- Relative Virtual Address calculation

- Export Address Table (EAT)

- Windows x64 calling-convention in practice

- Writing in Assembly like a real Giga-Chad...

What limitations does shellcode have?

Shellcode must be position independent. It must not assume any fixed addresses. Therefore, shellcode does not have access to functions that we normally execute in C with a single line of code. Shellcode must work everywhere without any dependencies!

The above statement leads us to the obvious conclusion that within a shellcode we cannot simply use GetProcAddress() and get the address of any WinAPI function... because we don't know the address of GetProcAddress() function itself.

In this post, we'll look at manually finding the address of the WinExec() function in kernel32.dll and executing the calc.exe program (Windows built-in calculator) to confirm that everything works.

Overview: How to find a WinAPI function manually?

All the basic WinAPI functions can be found in the kernel32.dll file. This module is loaded automatically into every newly created process memory in Windows. However, the base address of the kernel32.dll module in memory may be random.

Each process on Windows also contains a PEB (Process Environment Block) structure in its memory. The address of this structure is known and it all starts with it. This structure contains a lot of information about the process, including data about all loaded modules (including kernel32.dll). There we can find, among other things, the base memory address of the kernel32.dll module.

Then, by reading the structures of the PE file (kernel32.dll), we arrive at the Export Address Table, which contains the names and addresses of all the functions exported by the file.

This is how we find the address of the WinAPI function (WinExec). Then we are ready to execute it based on x64 calling convention and Microsoft's documentation.

That's the process in a nutshell: jumping through memory structures and pointers in search of our function. Let's see what it looks like in details...

Get address PEB structure

The first step is to find the address of the PEB structure. PEB (Process Environment Block) contains a lot of information about the current process. Key properties of the PEB include:

- Loaded Modules (

LDRfield: we want this!) - Environment Variables

- Command-Line Arguments

- Other information about the process

PEB structure is stored in a user-space of the process. That means, it can be manually read without any syscalls. For x64 architecture the PEB address is stored in the gs register + 0x60 offset. The fs and gs segment registers have no specific uses defined by the hardware so they are used in this case by Windows internals to hold important addresses.

mov rbx, gs:[0x60] ; Get address of PEB structGet address of PEB_LDR_DATA

PEB_LDR_DATA (PEB Loader Data) contains information about the loaded modules for the process. We need to access this structure to get an address of the kernel32.dll.

typedef struct _PEB {

BYTE Reserved1[2]; // 2 bytes

BYTE BeingDebugged; // 1 byte

BYTE Reserved2[1]; // 1 byte

PVOID Reserved3[2]; // 16 bytes

PPEB_LDR_DATA Ldr; // <-- We want this

// ...

}There are 20 bytes from the beginning of the PEB structure to the LDR field. However, this is not true! All because of a compilation phenomenon called data structure alignment. On 64-bit Windows the alignment of memory structures is typically 16 bytes. It doesn't matter in this case. But what matters is the fact that 64-bit pointers are aligned to a 8-byte boundary. It means, the address of the pointer in memory cannot be different than multiplication of 0x8. Let's count bytes before the PVOID Reserved3 field: 4 bytes! Reserved4 pointer must be alligned with 4 bytes to round up its address to 0x8 bytes. Read more about data structure alignment.

This is how the final PEB structure looks like (with padding included):

struct _PEB {

BYTE Reserved1[2]; // 2 bytes

BYTE BeingDebugged; // 1 byte

BYTE Reserved2[1]; // 1 byte

BYTE Padding[4]; // 4 bytes

PVOID Reserved3[2]; // 16 bytes

PPEB_LDR_DATA Ldr; // <-- We want this

// ...

};Now we can clearly see that we need 24 bytes (0x18) to get the LDR field. We extract the value of the field by dereferencing (square brackets):

mov rbx, [rbx+0x18] ; Get PEB_LDR_DATA addressGet addresses of loaded modules

Now when we have the PEB_LDR_DATA structure we need the address of the InMemoryOrderModuleList field:

struct _PEB_LDR_DATA {

BYTE Reserved1[8]; // 8 bytes

PVOID Reserved2[3]; // 24 bytes

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

};Get the address of InMemoryOrderModuleList (32 = 0x20 bytes):

add rbx, 0x20 ; Get address of InMemoryOrderModuleListLIST_ENTRY is actually the double-linked list. The first field (the one we've just extracted) is the pointer to the next list entry. By dereferencing addresses, we can get to individual items in the list. Go down the double-link list:

mov rbx, [rbx] ; 1st entry in InMemoryOrderModuleList (ntdll.dll)

mov rbx, [rbx] ; 2st entry in InMemoryOrderModuleList (kernelbase.dll)

mov rbx, [rbx] ; 3st entry in InMemoryOrderModuleList (kernel32.dll)The third entry is the kernel32.dll. I'm not sure if this is guaranteed, but this is how people have been doing it for centuries. Who am I to question that...

struct _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY {

..

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderLinks; // 16 bytes

PVOID Reserved2[2]; // 16 bytes

PVOID DllBase;

...

};As we go down the double-linked list (LIST_ENTRY) we are already at an offset of the beginning of the structure. Now we have to get the DllBase pointer. DllBase is the address of the DLL in memory!. The offset is 32 bytes (0x20):

mov r8, [rbx+0x20] ; Get the kernel32.dll addressNow we have kernel32.dll base address.

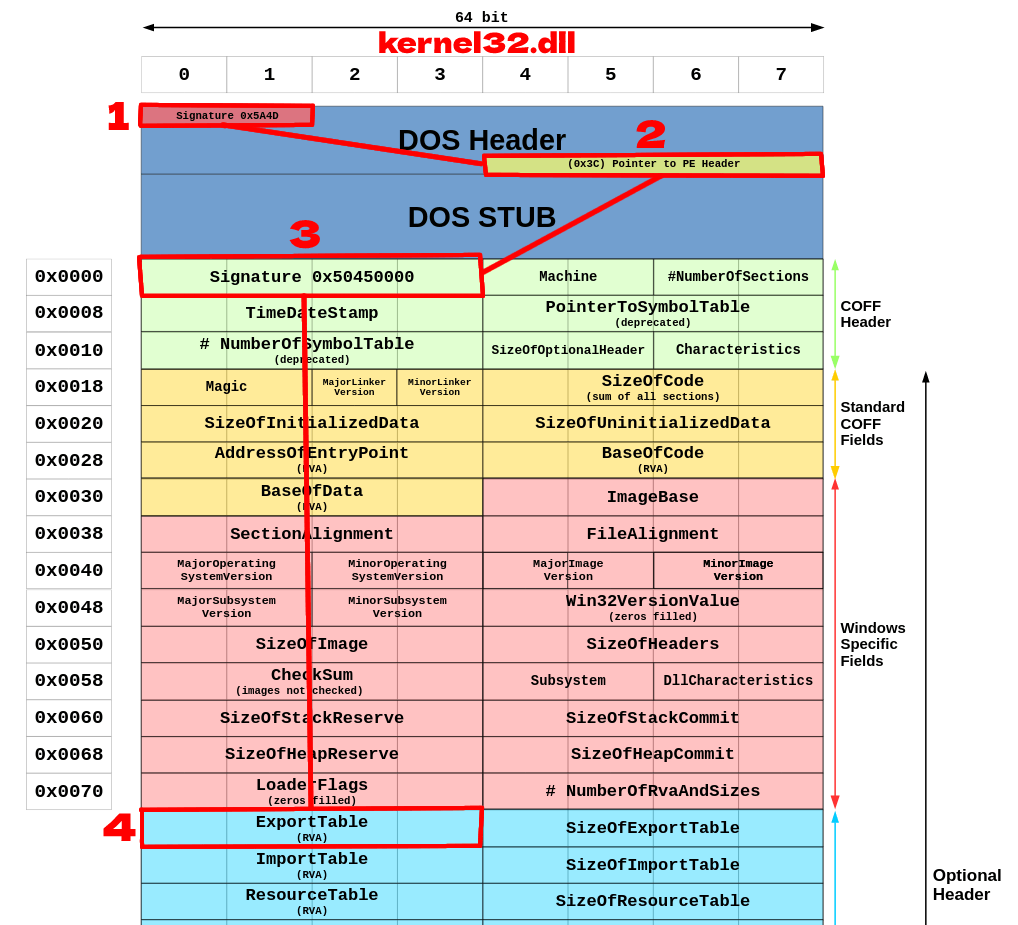

Get the address of ExportTable (kernel32.dll)

We need to get to the ExportTable of the kernel32.dll module to get information about the WinAPI functions it exports.

PE file structure (simplified):

- IMAGE_DOS_HEADER (we need to get

e_lfanewRVA) - DOS Stub (skip this)

- PE Headers (

kernel32.dllbase addr +e_lfanewRVA)- ExportTable (offset of PE Headers addr =

0x70)

- ExportTable (offset of PE Headers addr =

This is the path we need to follow:

Let's take a look at the IMAGE_DOS_HEADER. It's the first structure of any PE file:

typedef struct _IMAGE_DOS_HEADER { // DOS Header

WORD e_magic; // Magic number (2)

WORD e_cblp; // Bytes on last page of file (2)

WORD e_cp; // Pages in file (2)

WORD e_crlc; // Relocations (2)

WORD e_cparhdr; // Size of header in paragraphs (2)

WORD e_minalloc; // Minimum extra paragraphs needed (2)

WORD e_maxalloc; // Maximum extra paragraphs needed (2)

WORD e_ss; // Initial (relative) SS value (2)

WORD e_sp; // Initial SP value (2)

WORD e_csum; // Checksum (2)

WORD e_ip; // Initial IP value (2)

WORD e_cs; // Initial (relative) CS value (2)

WORD e_lfarlc; // File address of relocation table (2)

WORD e_ovno; // Overlay number (2)

WORD e_res[4]; // Reserved words (8)

WORD e_oemid; // OEM identifier (for e_oeminfo) (2)

WORD e_oeminfo; // OEM information; e_oemid specific (2)

WORD e_res2[10]; // Reserved words (20)

LONG e_lfanew; // File address of new exe header (4)

} IMAGE_DOS_HEADER, *PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER;We need to get to a value of e_lfanew field. It contains the RVA of the PE Headers (or New EXE Headers).

Relative Virtual Address: Many addresses within PE file structure are written in a form of Relative Virtual Address (RVA). It means they are relative to the beginning of the file in memory (base address). To calculate (absolute) Virtual Address we need to add the RVA address to the base address of

kernel32.dll.

mov ebx, [r8+0x3c] ; RBX = kernel32.IMAGE_DOS_HEADER.e_lfanew (PE hdrs offset)

add rbx, r8 ; RBX = PeHeaders offset + &kernel32.dll = &PeHeadersNow rbx stores the address of PE Headers. At offset 0x88 of PE Headers the ExportTable RVA is placed. It's a constant value. Using ExportTable RVA and kernel32.dll base address we are ready to access ExportTable.

xor rcx, rcx

add cx, 0x88 ; RCX = 0x88 (offset of ExportTable RVA)

add rbx, [rbx+rcx] ; RBX = &PeHeaders + offset of ExportTable RVA = ExportTable RVA

add rbx, r8 ; RBX = ExportTable RVA + &kernel32.dll = &ExportTable

mov r9, rbx ; R9 = &ExportTableGet the WinAPI function address from EAT

Now we have the address of the EAT structure. This structure contains all the information about exported functions. Using this structure we want to find an address of WinAPI function WinExec().

typedef struct _IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY {

DWORD Characteristics;

DWORD TimeDateStamp;

WORD MajorVersion;

WORD MinorVersion;

DWORD Name;

DWORD Base;

DWORD NumberOfFunctions;

DWORD NumberOfNames;

DWORD AddressOfFunctions; // RVA

DWORD AddressOfNames; // RVA

DWORD AddressOfNameOrdinals; // RVA

} IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY, *PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY;Before starting the search, we need to save the string with the name of the WinAPI function we're looking for. We can't do this traditionally in the read-only data section or something like that because all we have is just the .text section. We have to put everything on the stack!

The stack grows downward, and addresses are read upward, so we have to place our string inverted (WinExec\0 -> \0cexEniW). All letters are converted to hexadecimal values. At the beginning we push the null-terminator.

xor rax, rax

push rax ; STACK + null terminator (8)

mov rax, 0x00636578456E6957 ; RAX = function name = \0 + "cexEniW" (WinExec)

push rax ; STACK + function name address (8)

mov rbx, rsp ; RSI = &function_name

call get_winapi_funcNow we already have a pointer to the string with the function name.

WARNING: Now it's going to get a little complicated. I will not describe every line of assembly code. I will present the general concept and paste the code snippet at the end.

In general, all boils down to going through the entire array of pointers to function names (AddressOfNames) and comparing them with the pointer to our desired function name. Probably the most interesting part is the repe cmpsb command. It's used to compare two strings (pointers are kept in RDI and RSI registers).

Once we find the right function name, our counter (RAX register) holds its index. Using this index, we can refer to an item in the AddressOfNameOrdinals array. Using the Ordinal Number extracted from this array, we finally refer to the item in the array AddressOfFunctions. Here we obtain the RVA of the WinExec function, calculate the VA and return the address in the RAX register. And this is it! We have the address of the function we are looking for.

get_winapi_func:

; Requirements (preserved):

; R8 = &kernel32.dll

; R10 = &AddressOfFunctions (ExportTable)

; R11 = &AddressOfNames (ExportTable)

; R12 = &AddressOfNameOrdinals (ExportTable)

; Parameters (preserved):

; RBX = (char*) function_name

; RCX = (int) length of function_name string

; Returns:

; RAX = &function

;

; IMPORTANT: This function doesn't handle "not found" case!

; Infinite loop and access violation is possible.

xor rax, rax ; RAX = counter = 0

push rcx ; STACK + RCX (8) = preserve length of function_name string

; Loop through AddressOfNames array:

; array item = function name RVA (4 bytes)

loop:

xor rdi, rdi ; RDI = 0

mov rcx, [rsp] ; RCX = length of function_name string

mov rsi, rbx ; RSI = (char*) function_name

mov edi, [r11+rax*4] ; RDI = function name RVA

add rdi, r8 ; RDI = &FunctionName = function name RVA + &kernel32.dll

repe cmpsb ; Compare byte *RDI (array item str) and *RSI (param function name)

je resolve_func_addr ; Jump if exported function name == param function name

inc rax ; RAX = counter + 1

jmp short loop

resolve_func_addr:

pop rcx ; STACK - RCX (8) = remove length of function_name string

mov ax, [r12+rax*2] ; RAX = OrdinalNumber = &AddressOfNameOrdinals + (counter * 2)

mov eax, [r10+rax*4] ; RAX = function RVA = &AddressOfFunctions + (OrdinalNumber * 4)

add rax, r8 ; RAX = &function = function RVA + &kernel32.dll

ret Execute WinExec function

Here's what the definition of the WinExec function looks like (below). And we have a pointer to this function. Cool, isn't it?

UINT WinExec(

LPCSTR lpCmdLine, // => "calc.exe",0x0

UINT uCmdShow // => 0x1 = SW_SHOWNORMAL

);Now we just need to perform this function keeping in mind one very important thing: Windows x64 calling convention (documentation).

Three important requirements to work with WinAPI:

- Argument registers (from left to right):

RCX(lpCmdLine),RDX(uCmdShow),R8,R9, then stack... - 16-bytes Stack Alignment:

and rsp, -16 - Shadow space - 32 bytes long empty space allocated on stack for internal WinAPI usage:

sub rsp, 32

With the above rules in mind, we are preparing arguments. Again, the string with the name of the program to be executed (calc.exe) is pushed on the stack and the address to it is passed in the first parameter. We set the second parameter to SW_SHOWNORMAL value (0x1), which simply means show default process window.

xor rcx, rcx

xor rdx, rdx

push rcx ; STACK + null terminator (8)

mov rcx, 0x6578652e636c6163 ; RCX = "exe.clac" (command string: calc.exe)

push rcx ; STACK + command string (8)

mov rcx, rsp ; RCX = LPCSTR lpCmdLine

mov rdx, 0x1 ; RDX = UINT uCmdShow = 0x1 (SW_SHOWNORMAL)

and rsp, -16 ; 16-byte Stack Alignment

sub rsp, 32 ; STACK + 32 bytes (shadow space)

call r13 ; WinExec("calc.exe", SW_SHOWNORMAL)Done, we are ready to compile!

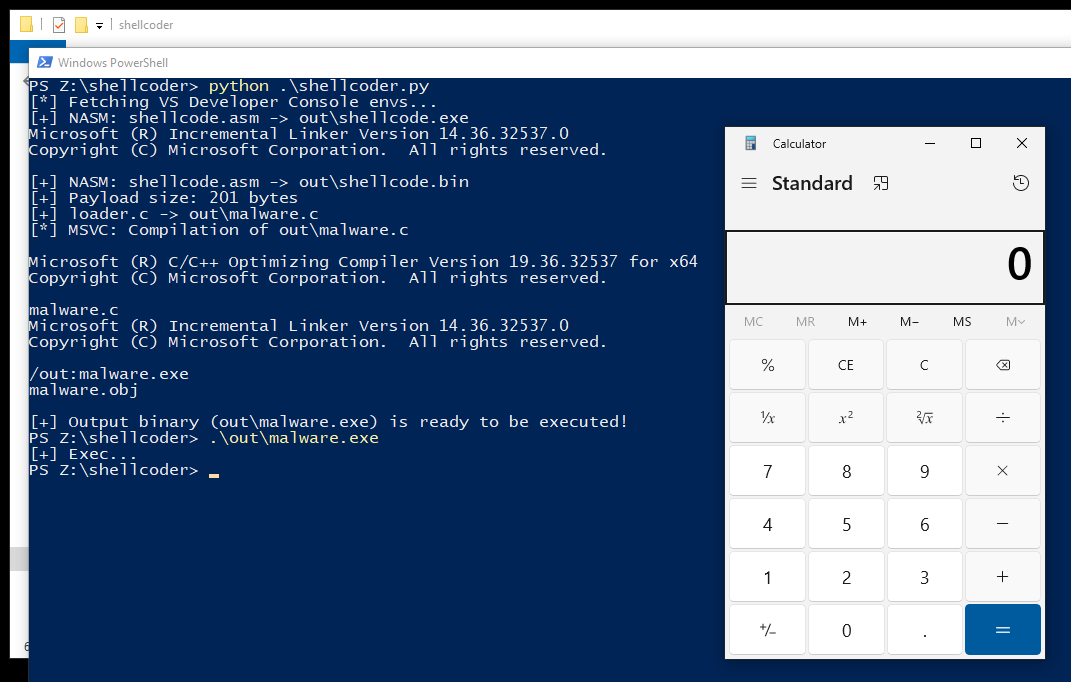

Compilation adn execution

I won't elaborate much here. I wrote a simple script in Python (shellcoder.py) that compiles the NASM code into an executable EXE format. This makes it very easy to debug our "shellcode", correct it and compile it again with one click.

After successful compilation, we are ready to run!

Nice.

Conclusion

Learning low-level access to WinAPI functions from within Assembly is extremely developmental. It allows you to better understand malware, of which shellcode is now often one of the main components. Unfortunately, for some reason, few people today are involved in writing shellcode. But those who write the shellcode themselves are Giga-Chads.

~ Print3M